The Tudor period, which lasted from 1485 through to 1603, saw an enormous amount of change in the form and function of the castle.

At the start of the period, traditional Medieval castles were falling into disrepair, and could not hope to withstand attack from newly developing gunpowder artillery – the 12th century Cahir Castle, widely considered to be the strongest in Ireland, was captured from Irish rebels by the Earl of Essex in 1599 after only a few days of bombardment.

Instead, new castles developed with thicker walls and squat towers that could house gunpowder weapons. However, while these new forts were highly effective military defences (as well as prestigious statements of power), they made for very uncomfortable homes.

As a result, palaces emerged as the favoured dwelling place of powerful lords and monarchs. It was in the Tudor period that the castle as both a noble residence and military fortification came to an end – instead, these two functions were separated and fulfilled by palaces and the newly developed forts respectively.

A Guide to Tudors, their Castles and Palaces

The Tudors

The House of Tudor was an English Royal dynasty of Welsh origin, which ruled England from 1485 until 1603. Six monarchs reigned during this period: Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey, Mary I, and Elizabeth I.

Henry VII claimed the throne through conquest during the Wars of the Roses between the rival royal houses of Lancaster and York – he positioned himself as a candidate for supporters of the Lancastrians, but also for disaffected supporters of the House of York.

Henry VII’s defeat of the Yorkist king Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field on 22nd August 1485 won him the crown of England, and his subsequent marriage to a Yorkist united the previously warring factions and secured his rule.

The beginning of the Tudor line effectively signalled the end of the Medieval period and ushered in the Early Modern era, which is generally agreed to have lasted from around 1500 until the year 1800.

The Early Modern period heralded a great deal of change regarding castle building, and as such the Tudors had a very different relationship with their castles than earlier English monarchs had.

The invention of gunpowder was the primary factor that drove change – although it had reached Europe in the 1300s, gunpowder technology only became advanced enough to seriously threaten castle walls in the 1400s.

Therefore, castles built in the 15th and 16th centuries developed thicker walls and round towers in order to be able to stand up to artillery fire, and in Italy a design known as the ‘Star Fort’ developed, which quickly spread all over Europe.

While these new castles and forts were effective at housing artillery, as well as defending against it, their thick walls and military design made them uncomfortable living spaces.

As a result, Tudor nobles and monarchs began to build great palaces to live in, luxurious and highly comfortable homes that were also statements of power and wealth.

Castles still served a defensive function, but the rise star forts meant that very few new traditional-style castles were built during the Tudor period, and a great many existing medieval castles fell into disuse and disrepair.

Effectively the dual military and residential functions that castles had fulfilled in the middle ages was ended – castles developed into purely military fortifications such as star forts, while palaces became the dwelling places of monarchs and nobles.

Tudor Castles

The decline of castles in England began before the rise of the Tudors. During the 15th century, the number of English barons began to decline, leading to a nobility that was smaller and wealthier.

Thanks to this, a great many regional castles began to fall into decline – the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485) were primarily decided by pitched battles, and castles did not play an important role.

The poet John Leland (d. 1552) wrote about many of these castles in his ‘Itineraries’, describing an overall picture of decay and disrepair. Although many of the fortifications still had their walls standing, the buildings inside were regularly falling apart due to disuse.

Royal castles also lacked the investment to keep them in good condition, as the crown was increasingly choosing to fund a select few castles – major regional castles such as York, Nottingham, Gloucester and Bristol were funded in order to maintain royal authority.

Despite the physical decline, some castles remained relevant by fulfilling an administrative or judicial role.

The royal regional castles previously mentioned were used as jails for criminals, and Ludlow Castle became the headquarters for the Council in the Marches of Wales, which evolved into a governmental and judicial body, effectively making Ludlow Castle the ruling seat of Wales.

However, although many of the medieval castles in Britain were neglected, there were some notable developments in Tudor castle building.

One example was so-called ‘tower houses’, typically square stone towers with crenellated battlements, which are very similar in appearance to stone keeps.

The intention of these towers was to act as an obstacle to enemy raiding parties – as they were relatively small, tower houses could not hope to offer much resistance to a determined enemy army, especially if it carried siege equipment.

Often the towers would have a small walled courtyard featuring a gateway with a metal gate known as a ‘yett’, but typically this was intended to house livestock rather than forming part of the defences.

Some towers had gunports large enough for artillery, but mostly these castles had small gunports for muskets and other handheld firearms.

A great many tower houses were constructed in the late Medieval period, and they continued to be built and used into the Tudor period, particularly during times of warfare or social upheaval.

For example, in 1494 James IV of Scotland revoked the title of Lord of the Isles from the MacDonalds, and in reaction, a spate of tower houses was built across the country. Similarly, Scottish wars with England in the 1540s saw many of these castles built on both sides of the border to hamper raiding efforts.

In Ireland, there were as many as 3,000 tower houses, along with 800 in Scotland and 250 in England.

Tower houses, like their medieval predecessors, also served another purpose for more minor, local lords: although smaller than the grand stone fortifications of the high middle ages, they were nonetheless a statement of wealth and power, designed to impress the local population as well as rival lords.

As siege technology and artillery design developed during the Tudor period, so too did castle construction. Round towers were increasingly utilised, for they had a greater chance of deflecting enemy artillery fire.

Towers were also built lower, to allow defenders to mount artillery on top of them. ‘Letterbox’ gunports also emerged – these were gun ports built into towers that would be covered by a screen mounted to the wall, that would be raised when the gun was ready to fire.

The caponier also developed a kind of covered passageway that would allow the garrison to access the outworks of a fortification without being exposed to enemy fire.

On the continent (and later on in England), bastions became a feature of fortifications. Bastions were structures that projected out from a curtain wall, usually angular in shape.

They afforded artillery a greater field of view across the defences and would also allow defenders to protect the curtain wall of a fortification by pouring fire down onto attacking soldiers.

Many of these developments reached England very slowly in the Tudor period. Rising tensions with France during the reign of Henry VIII led to the construction of a series of so-called ‘Device Forts’ which incorporated many aspects of new castle technology.

Typically, these forts were built in a trefoil or quatrefoil shape, made up of three or four overlapping circles. The intention behind this design was to allow the guns mounted in the fort to have a 360-degree line of sight – in addition to this, the towers were often positioned at different heights to allow the artillery pieces to fire simultaneously, without blocking each other’s view.

Although these Device Forts often featured bastions, they were semi-circular (see Deal Castle for an example), unlike the latest continental designs which were angular.

Device Forts marked a very definite shift away from earlier castles styles – these new forts were garrisoned and were solely military in function, built entirely without the kind of luxury accommodation that was so often a hallmark of the medieval castle.

They were uncomfortable to live in, simply not befitting an early medieval noble or monarch who was concerned with projecting an image of his or her power and prestige. This explains how palaces came to be so popular during the Tudor period.

Tudor Palaces

The word palace has ancient roots – the palaces on the Palatine Hill in Rome were seats of imperial power in the Roman empire, and the word comes to us from the French palais.

Simply put, a palace is a grand residence, and is usually associated with royalty or religious leadership. Within a Tudor context, the word palace refers exclusively to grand residences belonging to monarchs or bishops.

As castles and forts lost their residential function during the Tudor period, wealthy monarchs had the opportunity to construct opulent palaces with the latest fashions, creating a residence that was not only incredibly comfortable and luxurious, but that would also serve as a political statement and a display of wealth.

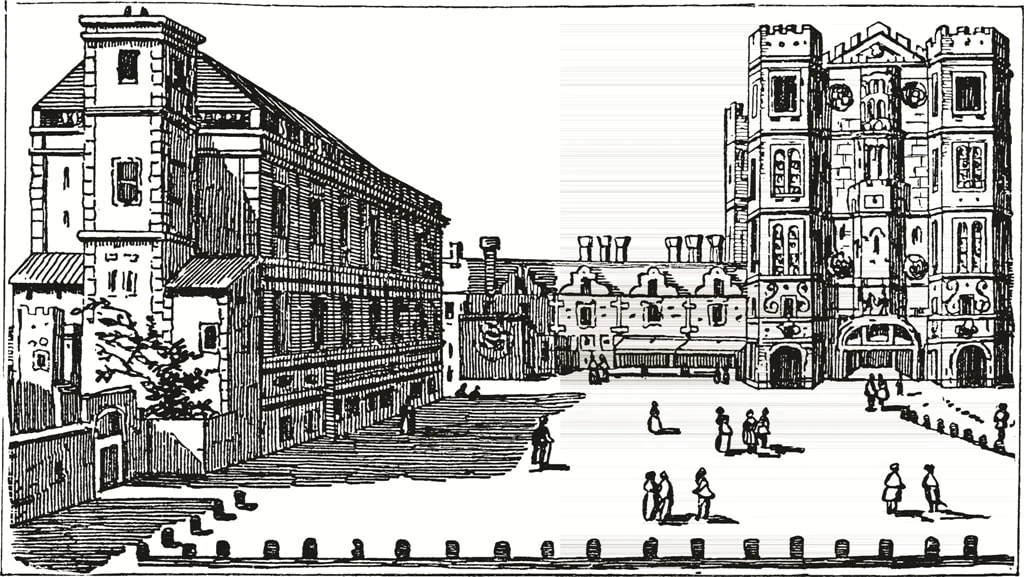

In many cases the grandest Tudor palaces had a gatehouse, which led through to an outer courtyard – it is not hard to see here how the palace design was influenced by elements of castle architecture.

The outer court would also be surrounded by buildings which could accommodate staff or guests, or offices for the palace staff. There would also be another gatehouse leading to an inner courtyard, around which would stand the most prestigious buildings, housing the highest status figures at court.

At Greenwich and Oatlands, this accommodation was situated in two buildings constructed opposite each other, running parallel to the inner courtyard.

At Richmond and Hampton Court Palace, these two buildings were stacked one on top of the other, forming one larger block. Lower status palaces would have a single courtyard, instead of the double-courtyard configuration described above.

Internally Tudor palaces had a series of distinctive features. There would be a Great Hall for dining purposes, and a passage at the lower end would provide staff with access to the kitchens.

At the high end of the hall, the lord of the house would dine with family or guests, sometimes on a raised platform in order to reinforce his or her higher status.

Naturally, these Great Halls, being reception spaces, were highly decorated, with elaborate woodwork, masonry and windows. Larger palaces would also have a door at the high end of the Great Hall that led through to the Great Watching Chamber, another finely decorated public room.

The Great Chamber had multiple functions, including being used as a dining space for senior officials and hosting various ceremonies. However, the primary function of this chamber was as a waiting room for members of the court and petitioners wishing to be heard by their lord.

As such, the chamber was watched over by members of the royal guard. Beyond the Great Watching Chamber was the final public room, the Presence Chamber, where a Tudor monarch would receive visitors and hear from ambassadors.

It was also the ultimate ceremonial space and was of course highly decorated – the king or queen would sit on a throne beneath a canopy at the high end of the room.

Henry VIII had his Presence Chambers bedecked with luxury carpets: the painting ‘The Family of Henry VIII’ depicts the Tudor monarch surrounded by symbols of his great wealth, in the Presence Chamber at the Palace of Whitehall.

It is clear to see how these opulent palaces, with their carefully planned ceremonial spaces, developed out of medieval castles. Palaces allowed Tudor monarchs to overcome the physical limitations that castles placed on ceremonial and symbolic architecture, with spectacular effect.

Beyond the public rooms, Tudor palaces also contained a series of prestigious private rooms. The Privy Chamber was the first of these, and only high-status individuals such as invited guests and the royal family would be able to gain access.

The Privy Chamber could be used for receptions but was also a private area to relax and dine in. It is also from this room that the innermost chambers of the palace could be reached.

Usually, there were two royal bedrooms, the larger ‘official’ bedroom, and a smaller one which the king used in practice. Some palaces, such as Hampton Court and Greenwich, even have a third bed-chamber.

Next to the bedroom would be a garderobe (toilet) and a closet, the smallest room used for private prayer, conversation and business.

Examples of Tudor Castles

Deal Castle

One of Henry VIII’s Device Forts, Deal castle was built in 1539-40 to protect England’s coast against the threat of invasion from France and the Holy Roman Empire.

Deal features a large central keep with six semi-circular bastions, as well as an outer moat. In total, the castle features sixty-six firing positions and has raised elements to ensure that artillery pieces would not block each other’s line of sight.

Deal, along with the forts at Sandown and Walmer, cost a total of £27,000 to construct, primarily funded through Henry VII’s dissolution of the monasteries.

St. Mawes Castle

Another Device Fort, St. Mawes was built near Falmouth between 1540-42 and defended the mouth of the river Fal. The castle is interesting in that it is built in a ‘clover leaf’ design: It has a four-storey circular central tower, with three round bastions attached.

These bastions vary in height to allow artillery pieces to fire over each other and have enough space to house nineteen guns. The fortification cost £5,000 to construct.

Aughnanure Castle

This tower house dates from the 16th century and was constructed by the O’Flaherty family of Connacht. It is an excellent example of a strong Irish tower house, with its great height, crenellated battlements, and machicolations (overhanging openings in the parapet that would allow defenders to drop objects and missiles onto attacking soldiers).

Craignethan Castle

Built during the first half of the 16th century, this Scottish castle is positioned on top of steeply sloping ground beside the river Nethan. Craignethan is a good example of an early artillery fort, featuring a 5-metre-thick wall to resist enemy gunfire, as well as gun loops to allow defenders to fire back.

Clonony Castle

An Irish tower house built by the MacCloughlan clan, Clonony boasts an imposing 50-foot tower with machicolations, murder holes, mural passages (within the walls), gun loops, spiral staircases, and walled courtyard. This incredibly well-designed tower house was ceded to Henry VIII by John Óg MacCoghlan.

Southsea Castle

This Device Fort has an interesting shape when compared with others that Henry VIII built – it has a square central keep, two rectangular gun platforms to the east and west, and two projecting bastions to the north and south. It is an early English example of the continental style of Bastion Fort or trace-italienne which became popular in the Tudor period.

Examples of Tudor Palaces

Hampton Court Palace

Henry VIII’s enormous and extremely lavish palace, Hampton Court originally belonged to his favourite courtier Thomas Wolsey, but was given back to the king in 1529 after Wolsey fell from favour.

The structure that stands there today is mainly the work of Wolsey (who spent 200,000 crowns to construct it), although Henry VIII added some elements to enlarge its capacity. The palace has a symmetrical plan with grand apartments, all finished with classical detailing in the renaissance style.

Greenwich Palace

Also known as ‘The Palace of Placentia’, Greenwich Palace was originally built by the Duke of Gloucester in the 15th century but was extensively rebuilt around the year 1500 by Henry VII and was modelled around three large courtyards.

Greenwich served as a royal palace until it was demolished in 1660 – Charles II’s palace that was intended to replace it was never completed.

The Palace of Whitehall

This vast palace was the primary residence of English kings from 1530 until 1622 – at its height it was expanded to contain 1,500 rooms, becoming the largest palace in Europe until Versailles was constructed.

Whitehall had always been the main London home of English kings, but Henry VIII made it his principal residence following a fire which destroyed much of the nearby Palace of Westminster.

The Banqueting House is the only integral building of the complex now standing.

Oatlands Palace

This Tudor royal palace, built by Henry VIII in 1538 for his wife Anne of Cleves, was based around three large courtyards, and also incorporated an existing 15th-century manor house.

Much of the stone used to build the palace was taken from the nearby ruin of Chertsey Abbey, which had fallen into a state of decay following the dissolution of the Monasteries.